6 things to consider when building an API

Web APIs are critical in creating reusable and interoperable software systems, not only within but also between organizations. Among other things, the understanding that IT is an asset that can enable strategic initiatives and even direct monetization is leading to a surge in API development. Just looking at publicly available APIs, thousands of new ones are published every year, according to ProgrammableWeb. Whether it’s to revitalize legacy software, decouple a software architecture, monetize functional or data assets, or roll out IoT applications, APIs can provide strong strategic advantages. However, when creating APIs, the risk of losing traction with users is significant.

APIs make data and functionality available to other applications. People developing these consuming applications (let’s call them ‘consumers’) expect clarity and stability. In almost any context, consumers are not under the direct control of the API itself. So, from the API ‘provider’ perspective, this requires a high level of maturity to achieve success.

It’s helpful to think of APIs as a typical UI, and then consider the importance of good UI design. When interacting with any UI, users will expect the interaction to be efficient, pleasant, and straightforward. A good interface goes out of its way to provide a seamless experience, because it builds trust and loyalty among end users. It prevents flocking to alternatives that offer better solutions. An API might not be as visible as a UI, and its end users might be developers, but other than that, they’re both interfaces and should both be treated as such.

Let’s discuss six themes that are essential to achieving solid, successful API implementations and highlight similarities to UIs to help better convey these ideas.

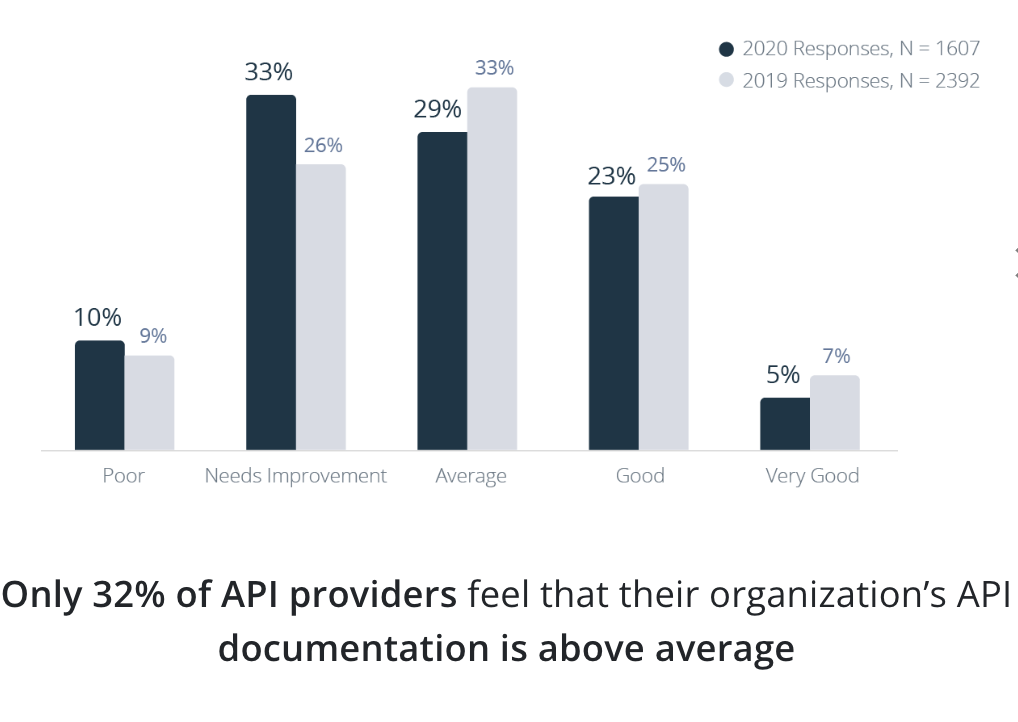

#1: Documentation

Despite all the hard work put into optimizing user interfaces, some features remain well-hidden. As a frequent user of all sorts of software ranging from the Office suite, my banking app, and Photoshop, I find myself looking up how to do things quite frequently. Especially if I’m new to a product. Search results vary. But the best results include official documentation and up-to-date guides.

A user interface doesn’t always need explicit documentation. The visual nature makes it self-documenting for the most important functionality. An API, however, is lost without good documentation, because API endpoints don’t have visible buttons and dropdown menus.

Developers of consuming applications will need guidance to understand the available functionality, the data required, and the data returned. Documentation is key. Luckily, there are more and more ways to generate the documentation and to make sure it stays in line with the actual implementation. Swagger, Stoplight, and Postman, to name a few.

If you really want to do good, provide developers with an interactive sandbox, like the one from Spotify to play around with actual API calls.

UI comparison: API documentation is practically the same as user manuals and tutorials.

#2: Easy onboarding

There’s only one overarching reason for exposing an API: So that other parties can integrate their software with yours. If no one does that, your API is dead in the water.

Bad documentation is just one common reason for failing adoption. Other reasons, according to TechBeacon, include forsaking industry best practices, lack of community-building, and forgetting about the developer experience.

To avoid disgruntled API consumers or having no consumers at all, focus on standardization and consistency. By laying a foundation in following common practices, effort can be put towards providing the actual value of the API. Consistent error messages, predictable data formats, and endpoint naming conventions can all work towards a happy developer experience.

These practices may not form the core value of the interface, but can in fact make or break it. In a competing ecosystem it might give one platform the leading edge over another, simply because consumers have a lot to gain from interaction with a highly standardized product. It can save precious time both in development and maintenance of code that needs to interact with the API, and speeds up initial onboarding.

The latest State of API report by SmartBear listed standardization as the top API technology challenge, as it was pointed out by 58% of the respondents. Just a few years back, in 2016, this was only 25%. It’s clearly become increasingly important.

UI comparison: This is like perfecting the intuitiveness of menus, buttons, and page layouts.

#3: Stability

Software changes. That’s a given. In software engineering, various patterns are used to minimize the potential impact of changes. The challenge is altering one piece of code without breaking some other code that might rely on it. But every now and then, the interaction between pieces of functionality has to change too.

Because the API provider has no direct control over its consumers, a clear versioning strategy is key. Breaking changes, including removal of functionality, need to be communicated timely. Whenever possible, new versions of an API should be backwards compatible. To allow for more significant alterations, it is all about communicating to consumers about ongoing and upcoming changes.

Consumers need time to adapt, and are not to be blindsided. Leveraging multiple communication channels is therefore recommended. For starters, documentation should include information about version life cycles. Additionally, more direct contact with customers can be sought, for instance, via online communities. In addition, there are many examples of APIs returning meta-information on versioning within the actual API responses, where developers will surely notice.

UI comparison: You wouldn’t suddenly move main UI elements across a view, and if you do, you’d probably let end users know through a tooltip or release notes.

#4: Ease of use

Even if you document things well, follow the conventions, and communicate clearly about changes from one API version to another, you could still end up with an interface that just doesn’t cut it. Especially if the interface is serving a variety of consumers with varying needs, it could be hard to design something that fits every use case.

Take the following example, based on a real case.

Say a television provider has a number of backend systems that host on-demand video, offer streams of live broadcasts, program guides, and more. The same provider has teams developing a number of user-facing applications, ranging from set-top boxes (STB, the box connected to your TV), a browser application, and mobile apps for a number of platforms. Broadly speaking, these frontends have roughly the same functionality. But there are important differences.

Firstly, the STB displays a widescreen landscape-oriented program guide showing ten channels vertically and four hours of content horizontally. There is plenty of space for that on a TV. The mobile app on the other hand is likely built for portrait orientation, showing no more than four channels spanning one hour in time. Secondly, on the STB, a user would maybe scroll down in steps of ten channels by pressing a button. Whilst in the app, users instead are used to scrolling smoothly and fast using touch gestures. Thirdly, the STB may show some short description about each program right in the guide view, whereas the phone may not have the screen real estate for that.

But differences extend beyond the views. For instance, an STB has constant power, but for a mobile app, battery consumption is a real consideration. It should be clear the interaction and non-functional factors differ between set-top boxes and mobile apps.

As an API provider you should allow for variance in use cases, by offering flexibility within the API. Sticking with the example above, a good implementation should consider the fact that consumers would like to paginate responses containing programming guide data (like allowing the request of either five, or ten, or 20 channels). This could be useful in lowering loading times, optimizing responsiveness, and limiting battery usage in the mobile app. To further optimize, the API could make fields in the response optional, and could offer sorted responses.

UI comparison: In many software products, users can customize and save their UI to better suit their needs.

#5: Encapsulation

A pit stop crew in Formula 1 racing comprises of roughly 20 people. This team is capable of lifting both front and rear jacks of the car, loosening the nuts on four wheels, taking away the old tires, bringing in the new ones, tightening the new wheels, and releasing the car.

In just two seconds.

This is a great example of encapsulating responsibility in real life. Each mechanic has a very specific task, and might interact with one or two of his peers. What happens beyond that, is none of their concern. As a result, the whole process is mind-blowingly flawless.

In a services landscape with a multitude of systems communicating through APIs, having clearly separated concerns is essential to avoiding one service requiring unnecessary knowledge of another. Behind these services are development teams that should not be bothered with implementation details except their own. API consumers want to spend time and effort creating value in their own products, thinking about why to use an external service. Not so much on figuring out how to integrate.

The goal here is to ensure points of integration only exchange necessary information. This goes both ways. A request should not be required to contain data that will not be used to handle the request. On the flipside, an API should not return data that was not requested (or should do so only with good reason). Providers should also be wary of violating more generic software encapsulation and security principles, such as leaking implementation details in error messages.

UI comparison: If you fill in an insurance policy form, you expect it to be a smooth experience requiring only the necessary information.

#6: Efficiency

Ultimately, APIs form a layer through which data is passed. Since this data is typically sent over a network, performance and reliability are crucial. Additional concerns like battery life, latency, storage, and data transfer costs may be relevant depending on context. Thus, achieving the required synergy between systems with as little communication as possible is beneficial.

Various strategies exist to limit the data flowing between applications. Caching comes to mind, as well as compression of payloads. Content distribution networks (CDNs) can be used to offload certain requests and to serve content timelier and more efficiently.

Observability is key to improving efficiency. Similar to monitoring and optimizing web applications to connect better to visitors’ needs, API usage can be monitored with various API management tools, as I explained in my last blog. Such tools can give valuable insight into performance and reliability aspects (like successful hits per endpoint, response times, and typical usage scenarios of consumers). Observability is the starting point to improving efficiency, and understanding how to evolve APIs in line with consumer demands.

UI comparison: Frequently-used practices to make UIs efficient are minimizing the number of clicks required to complete an action, avoiding nested menus, and providing short-cuts.

Final thoughts

To conclude, organizations designing and implementing APIs should realize that their APIs are real products with actual users. Aspects that need to be addressed aren’t unlike those that are important for creating successful user interfaces. When reasoning about APIs, it’s helpful to draw parallels to UI design, but of course the comparison only goes so far; as such, it’s mostly a way to make the topic more tangible. Since APIs expose services with the intention for others to adopt and use them, it’s up to the provider to adopt mature practices that drive success. Responsibilities include proper documentation, easy onboarding, stability, hiding unnecessary details, ease of use, and efficiency.

By holding APIs to high standards, organizations can increase the chances of creating truly value-adding, widely-adopted interfaces that cater to the organizational strategies. When done right, APIs can transform business models or even create entirely new ones.